Volume normalization in music streaming services

A while back, I started listening more to music with CDs. I’ve always been an avid enjoyer of music and I want to support artists as best I can so buying CDs during shows is something I like doing.

But then, something struck me, the music sounded better, way better, on CD compared to Tidal, which is supposed to deliver lossless, 16 bit per sample, 44.1kHz recordings, the same standard as CDs. With a bit of fiddling around the settings, I tried to remove the volume normalization option, and golly gee, the richness and the warmth came back.

But then why? I figured I needed an experimental setup to check what happens. Here’s the rough idea: First, record the output of CD recording, Tidal lossless with volume normalization and Tidal lossless without volume normalization. Then, import these recordings in Python and take a look at the distribution of power in the different frequency bands across time.

Recording

To perform the recording, since only my desktop Windows machine has a CD player, I used it. With Audacity, it’s not too bad, you can put loopbacks using the WASAPI interface.

The most important part is to record both with and without volume normalization using the same sound settings. Same volume everywhere so as not to introduce any bias. We also want to try to have settings that match as best we can for the CD recording.

Another trick that will help us down the line is to record some silence before the actual recording. Since we will be recording the same audio file, it will be the same length so syncing the start is the only thing we need to worry about and having some silence is an easy way to get that.

Looking at the recordings directly, the main difference we see is the magnitude of the signal. Whether this is the reason of the degraded sound quality or not is something we’ll investigate next.

Once everything is recorded, you can export in Audacity. It has an option to export per track and cut the leading silence so everything is very easy. As a format, I chose WAV with 16bit PCM, 44.1kHz.

Analysis

Cool, we have our data. Now we can analyze it. I use Python because it’s what I know best, but the principles can apply elsewhere too. For reference, the track I used for this analysis is Bomb.com from RedHook, from the album Mutation, which is quite an energetic track, with loud drums, vocals, guitar and bass as well as some electronic parts, with loud and some more quiet parts.

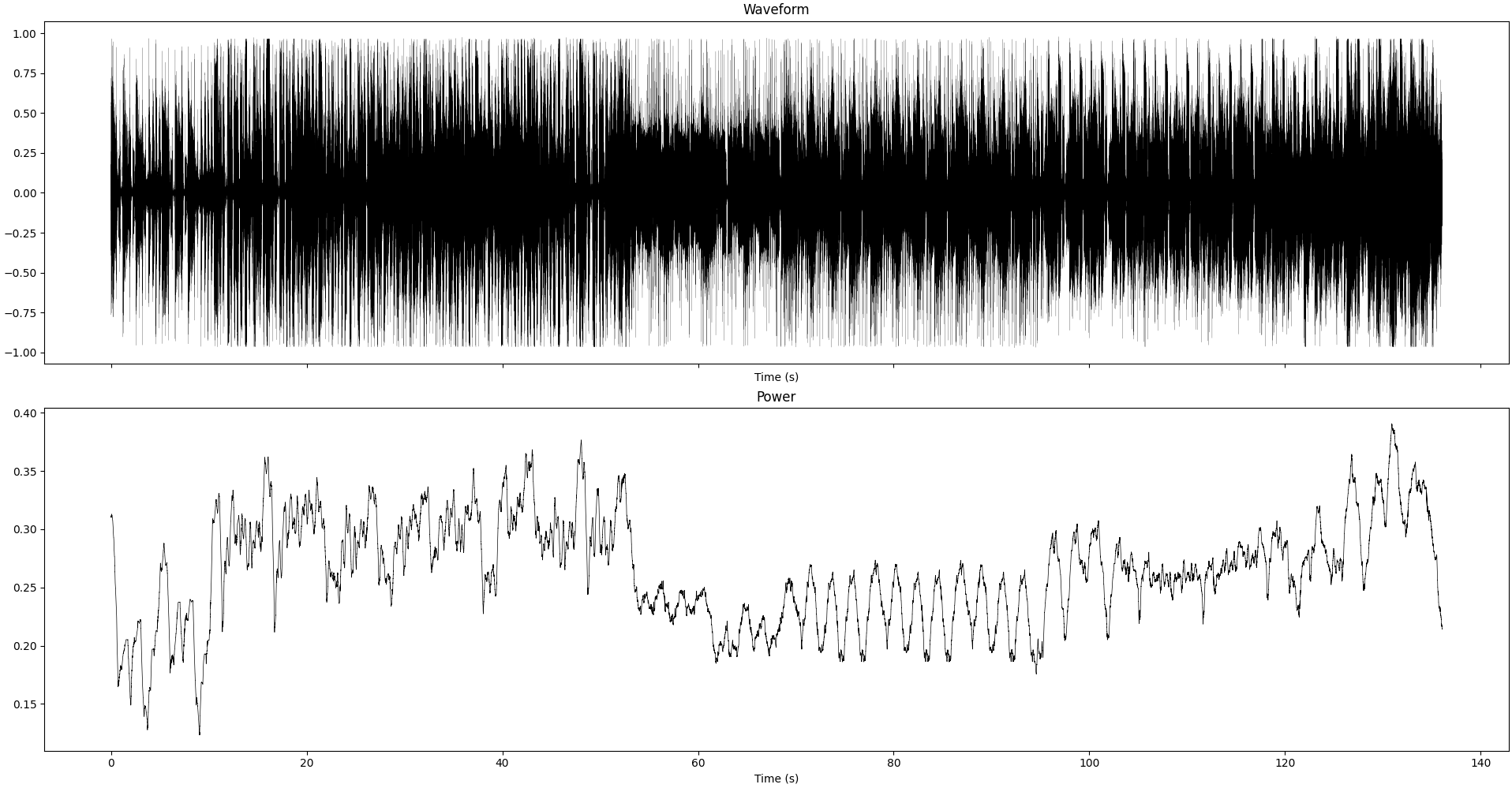

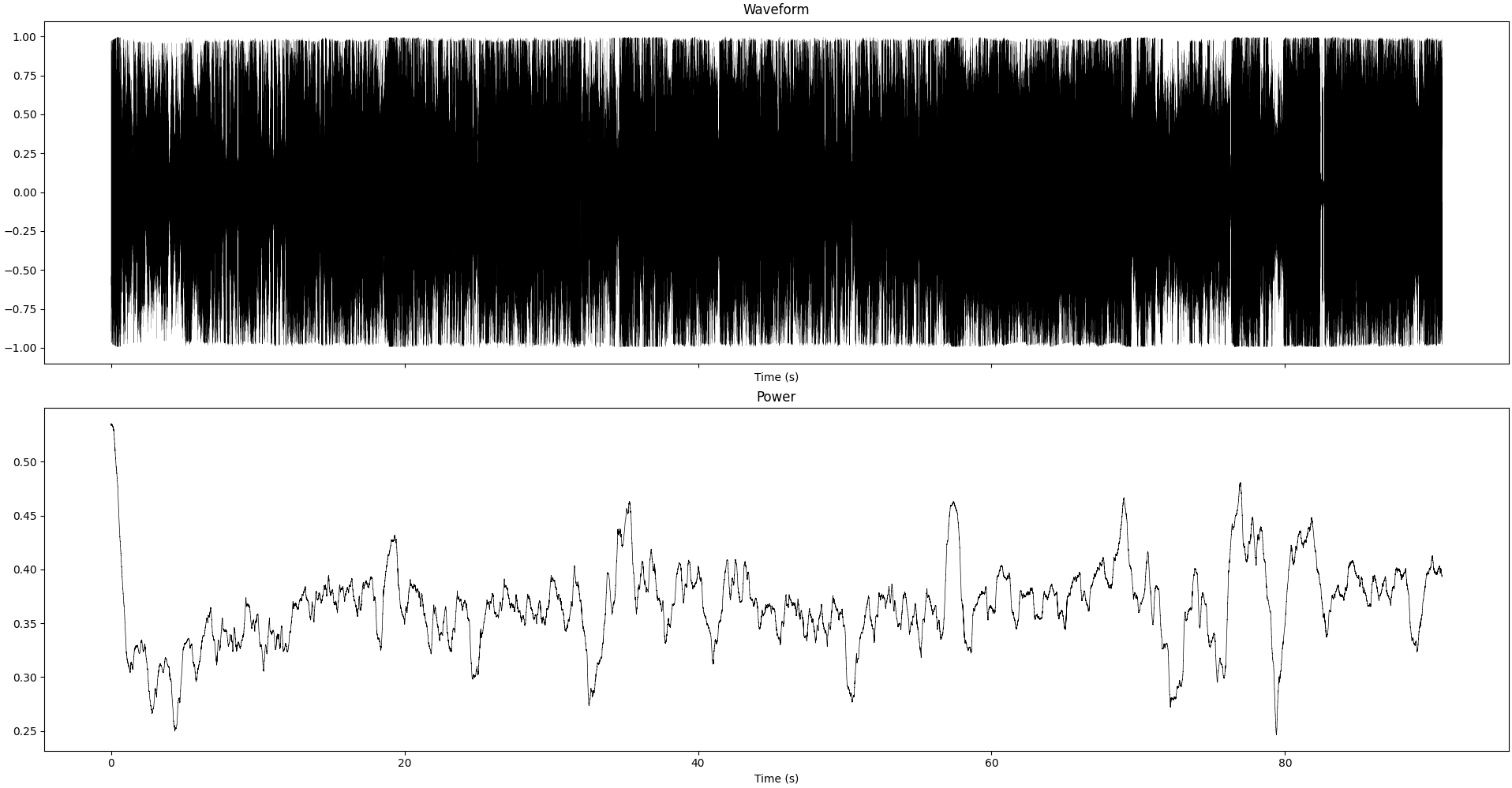

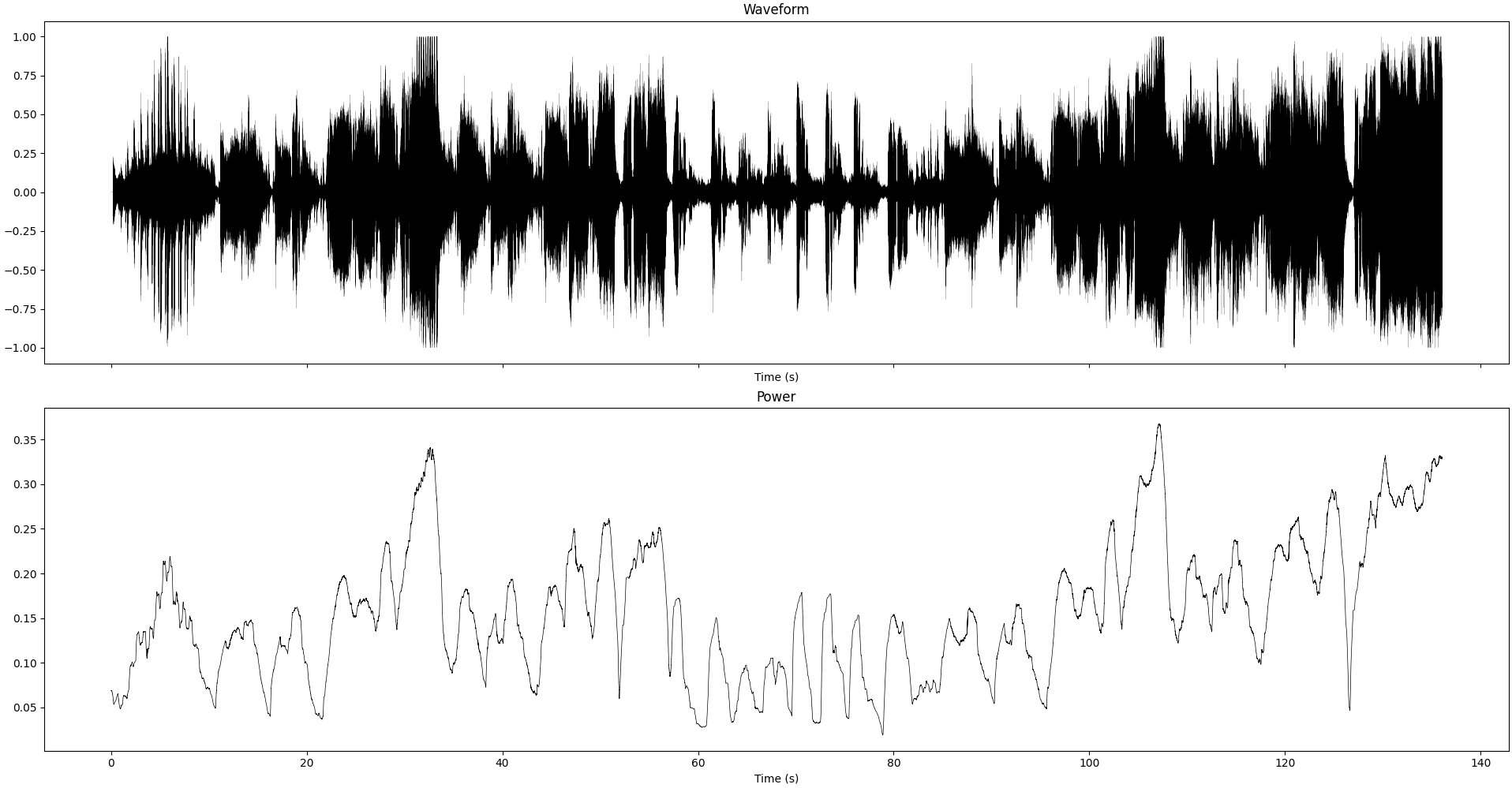

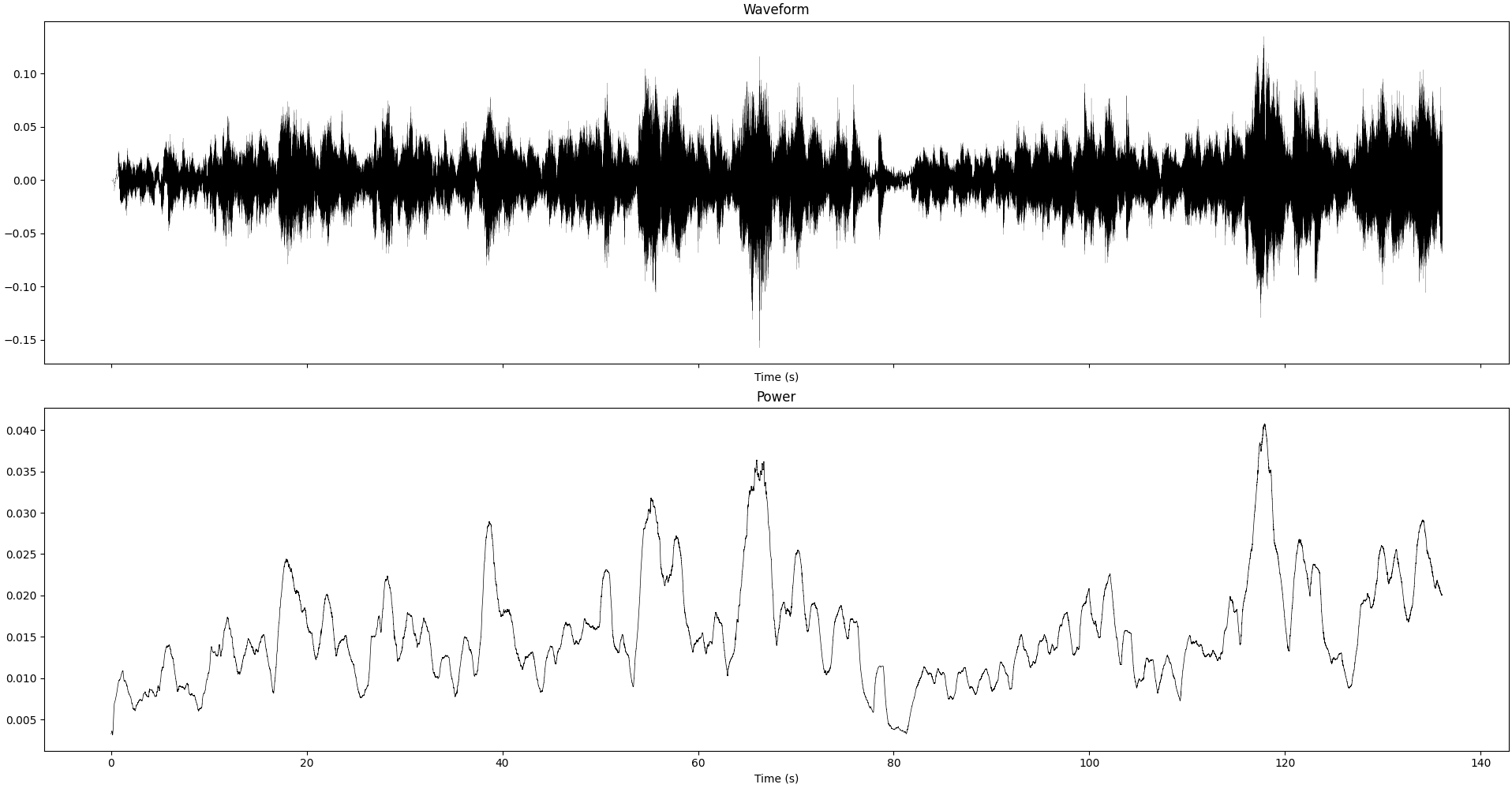

Waveform and instantaneous power (smoothed over 1sec) of the recording we study in this section

Waveform and instantaneous power (smoothed over 1sec) of the recording we study in this section

For importing the files, scipy.io.wavfile.read is a very good interface, it gives the sampling rate and the data in the form of a numpy array, with both channels.

For analyzing, I used scipy.signal.ShortTimeFFT, with a 1024-length Hamming window, 256 hop. Then, extract the spectrogram, convert it to dB: $A_{dB} = 20*\log A$, clipping at -200dB (10^-10 amplitude) for numerical stability.

Looking at the spectrograms directly, nothing is striking directly. But when looking at some higher-frequency harmonics, it seems to fade faster in the volume-normalized recording.

One thing I’m used to doing (mainly because it’s what we do when working on brain waves), is to cut the signal in different frequency bands and study how they relate to each other. For the human hearing, we usually think of “bass” (<250Hz), “mid” (between 250Hz and 4kHz) and “treble” (>4kHz). I needed something a bit less coarse so I settled on this division. Arguably it’s very arbitrary and we don’t really care that much about the exact thresholds, but it will give us a base that is sensible enough.

With this in mind, we can compute the average power in each band for the different recordings and see if there is something different.

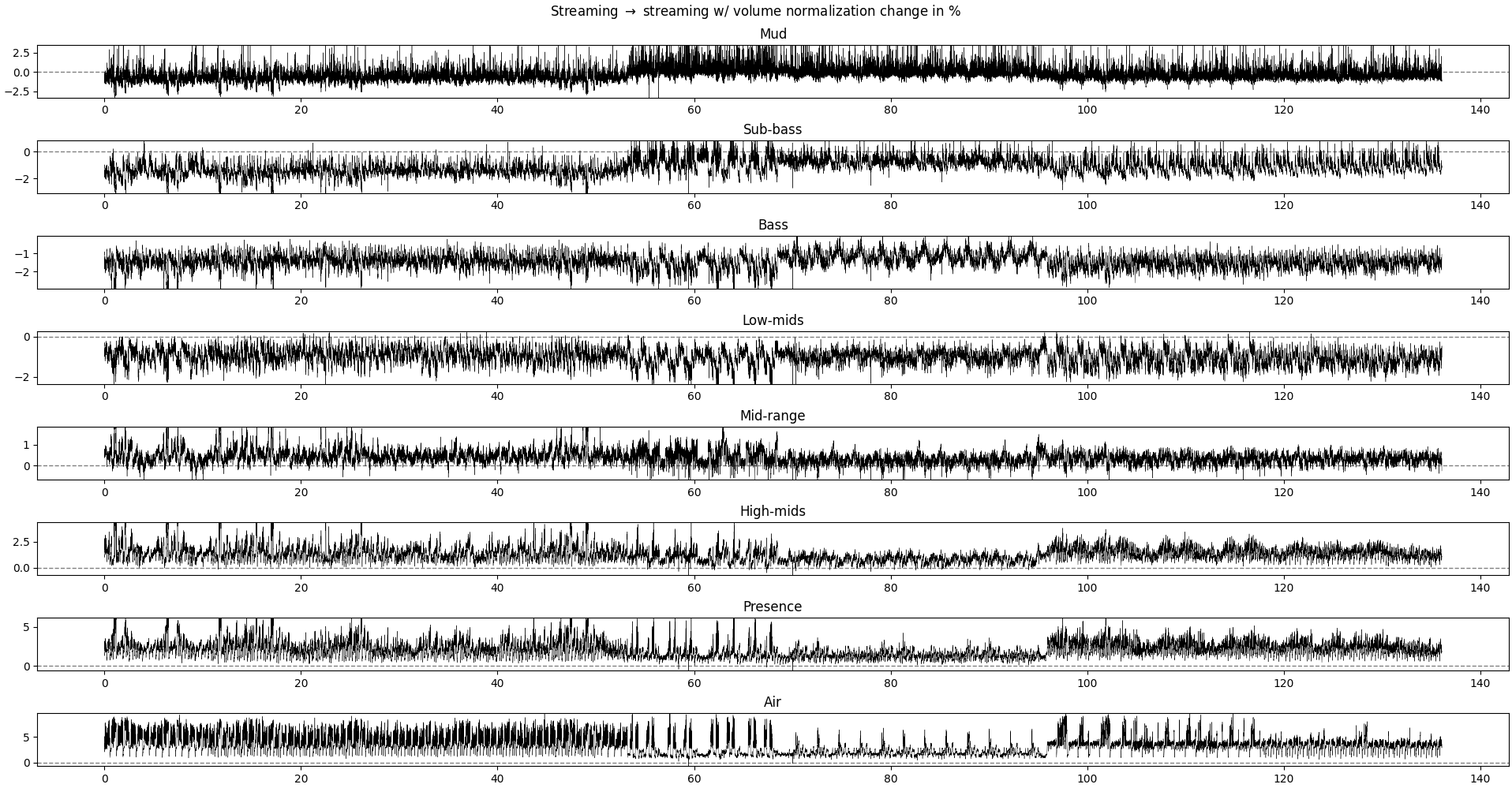

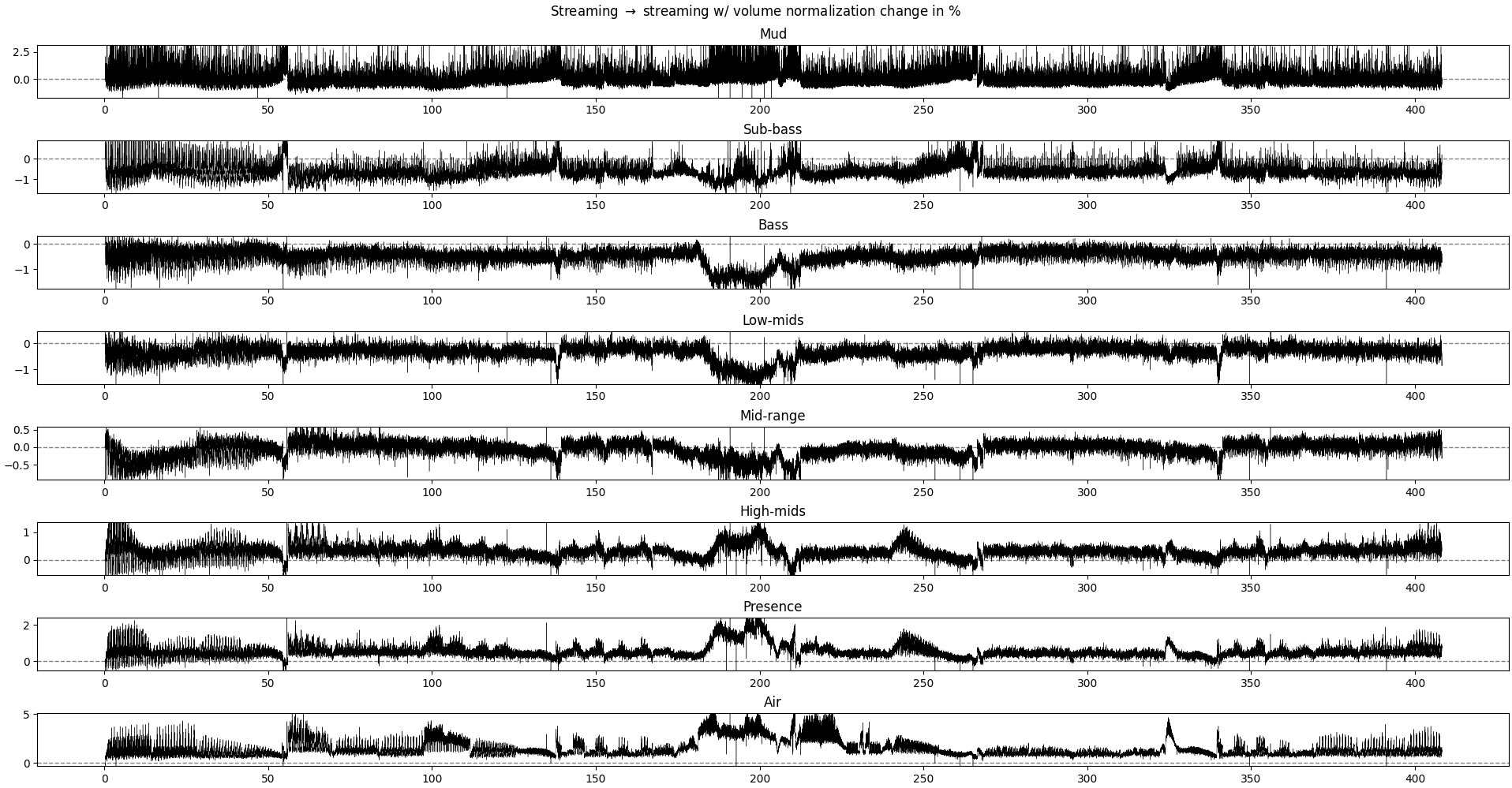

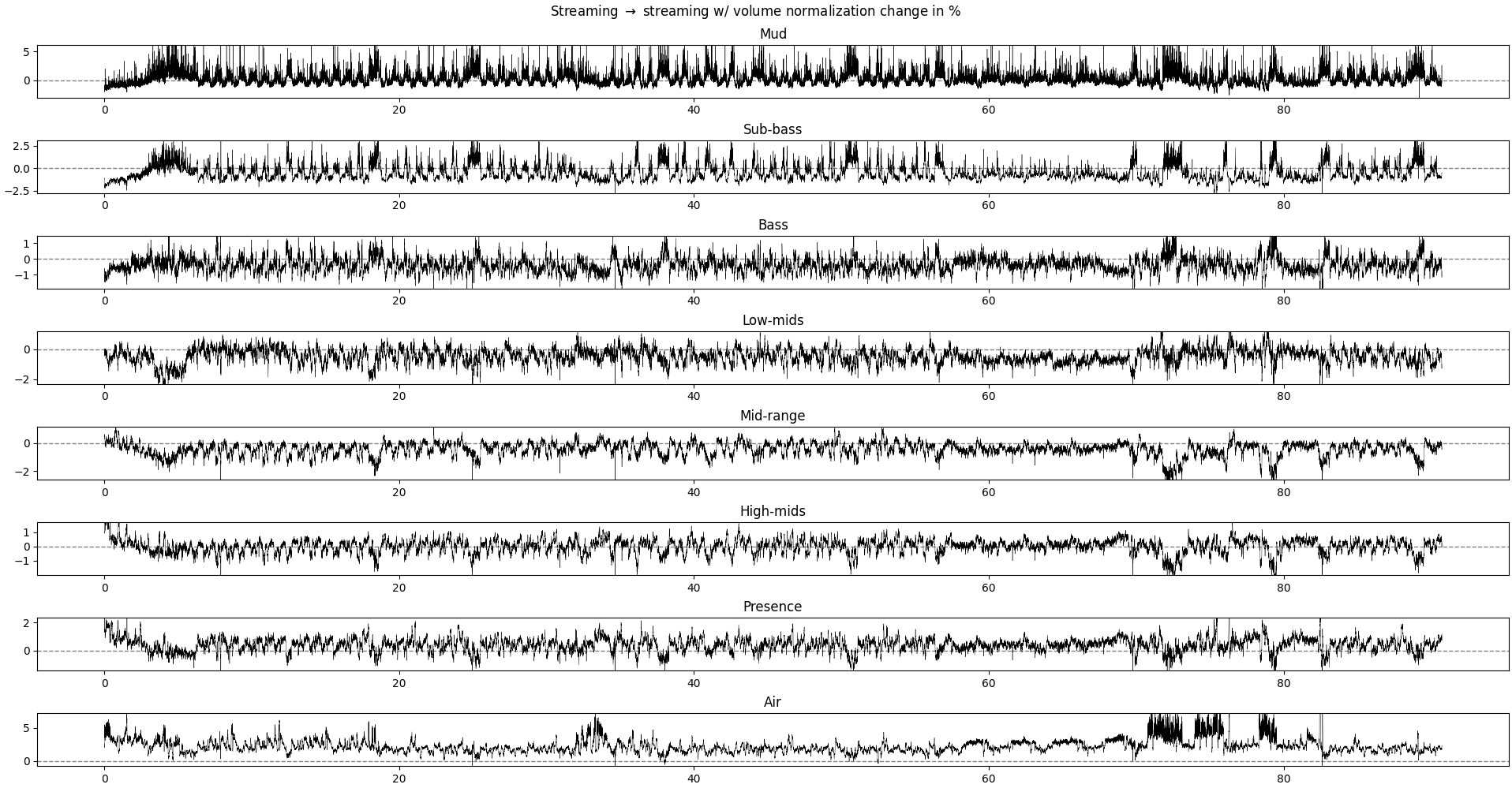

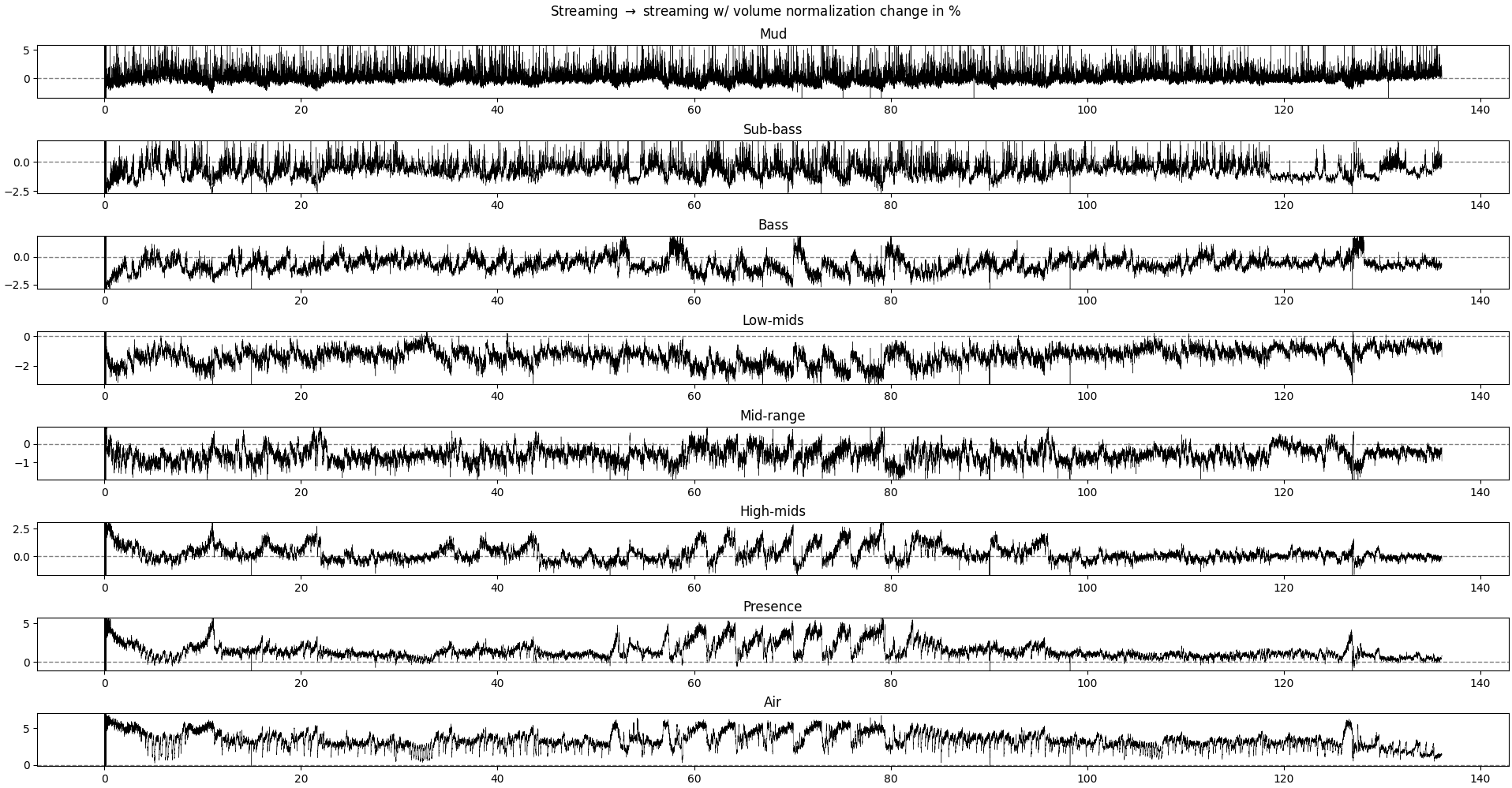

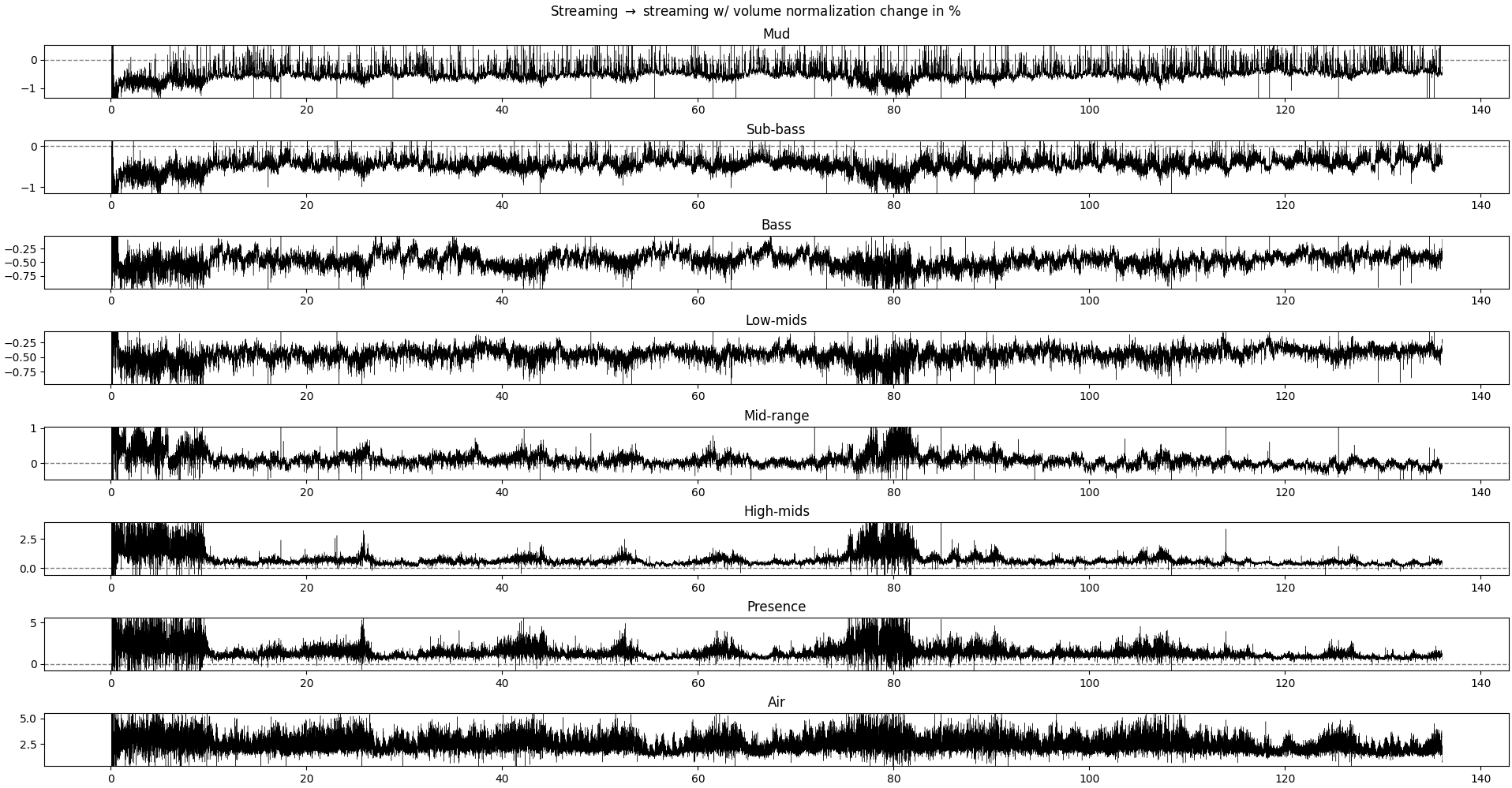

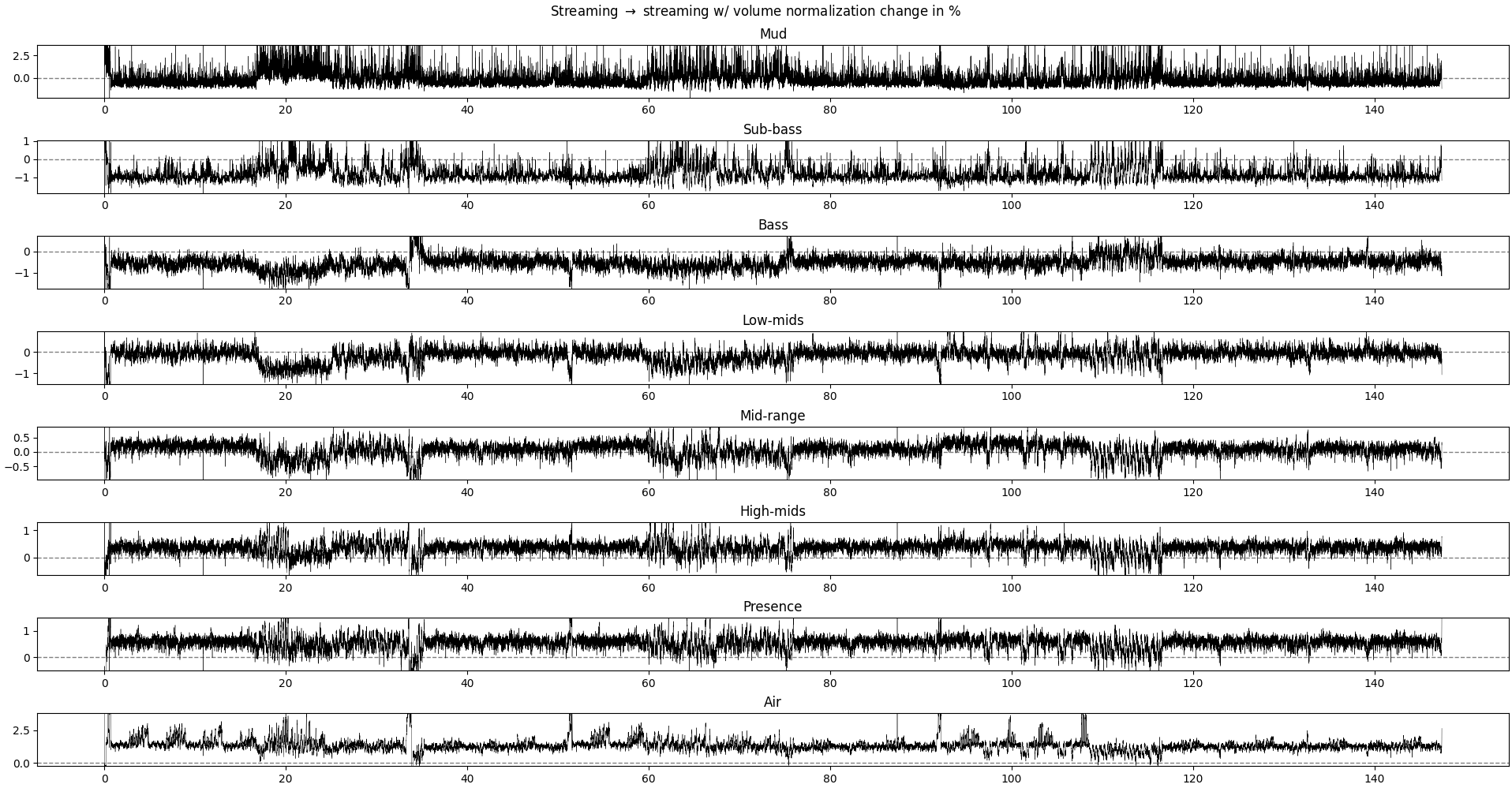

Plot of the relative difference between the relative power of each frequency band without and with volume normalization.

Each row is a different frequency band. Positive values mean that the recording without volume normalization has more relative power in this frequency band.

Plot of the relative difference between the relative power of each frequency band without and with volume normalization.

Each row is a different frequency band. Positive values mean that the recording without volume normalization has more relative power in this frequency band.

What we could expect if the volume normalization operation is a simple rescaling of the signal, without modulation across time, would be a (near-)1zero difference in all frequency bands, as we are looking at the relative power in each frequency band. The overall power may change, but not its distribution across frequencies.

We see differences of about 1-3% depending on the frequency band. The interesting result is that:

- for ranges 20-4kHz (sub-bass to mid-range), the volume-normalized recording is stronger

- for the lower and higher ranges, the non-volume-normalized recording is a bit higher

- at certain parts of the music, the non-volume-normalized recording has peaks in both low- and high-range frequency

So, what this means is that, in practice, volume-normalization tends to smother the ends of the spectrum, leading to a more muffled sound. The effects are not super big, but enough to be noticeable with some decent equipment (even a 80$ bluetooth headset can make the difference).

Let’s take another approach to confirm what we see here. Instead of comparing the relative power of frequency bands, we can compute the gain on each frequency band (instead of doing $(P_1 - P_2) / P_1$, we do $P_2/P_1$, and express the result in dB).

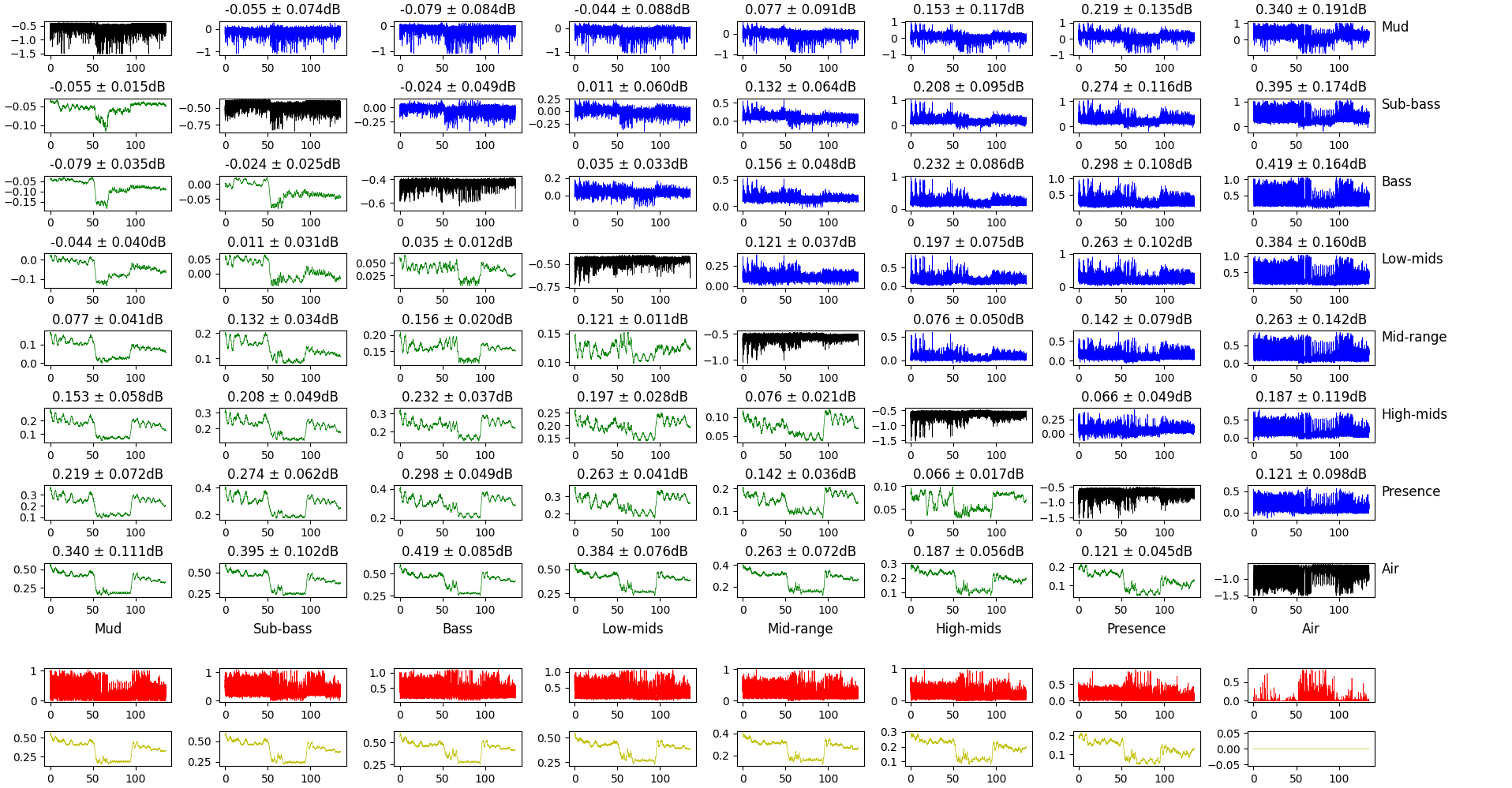

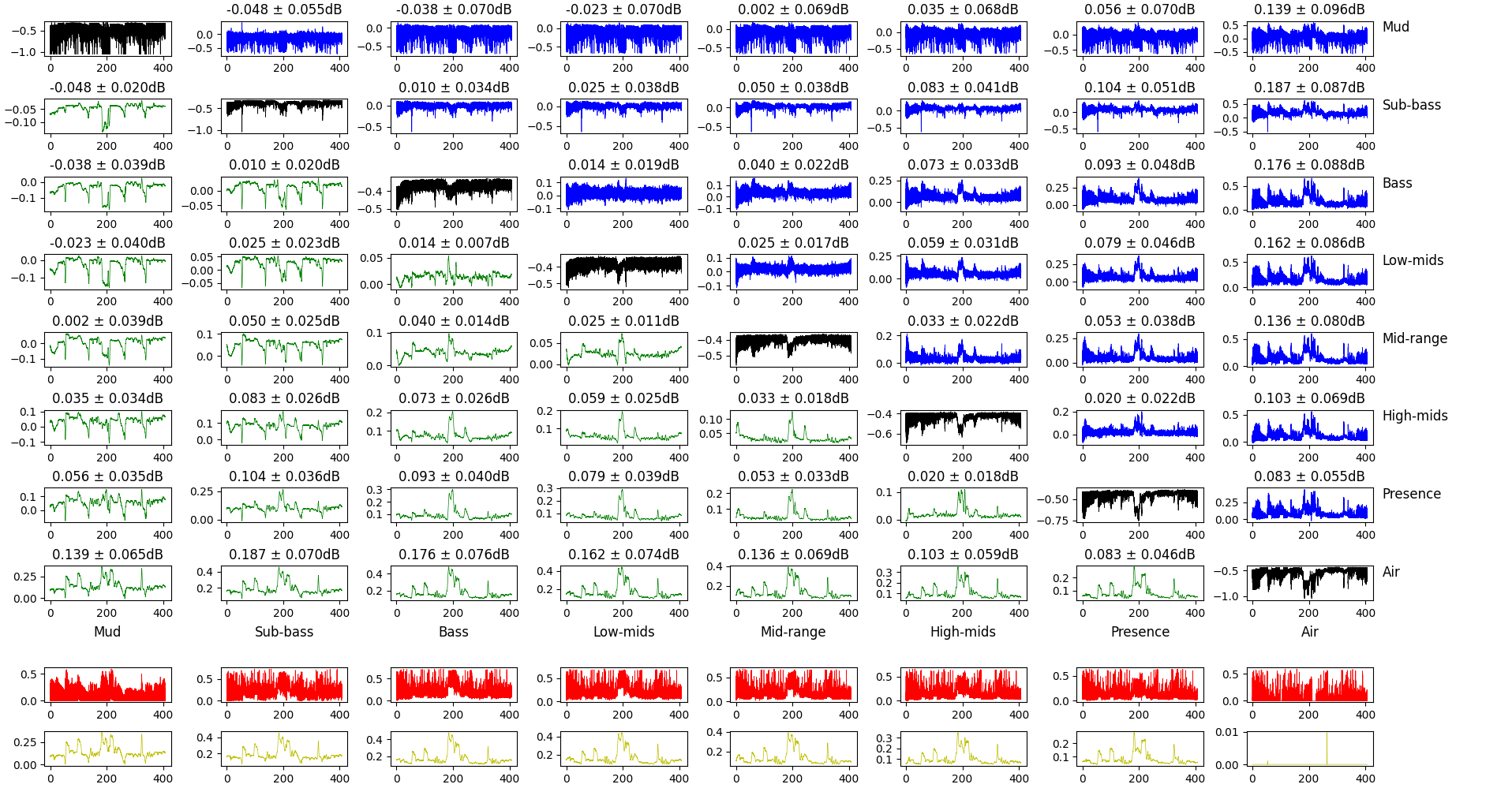

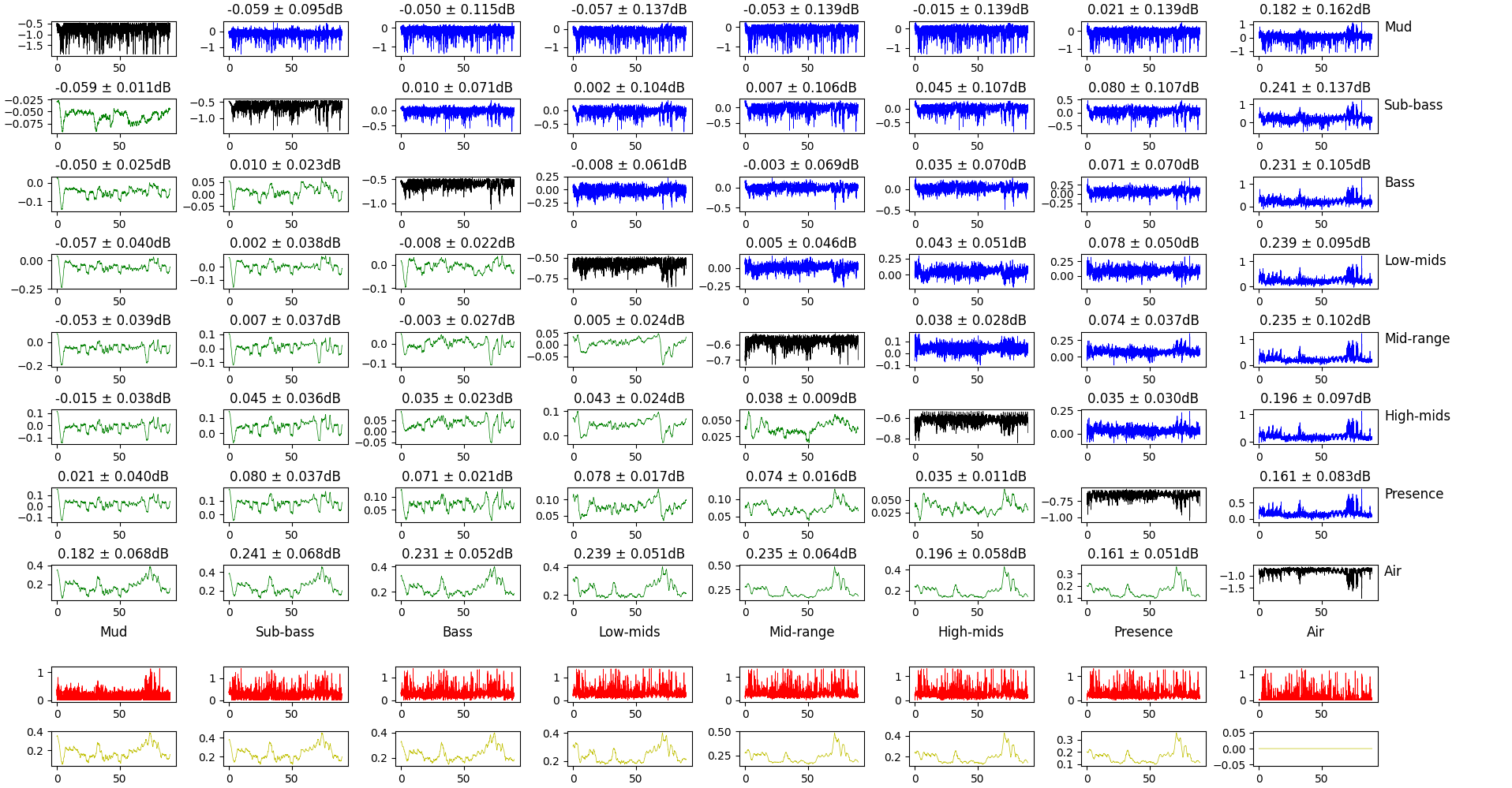

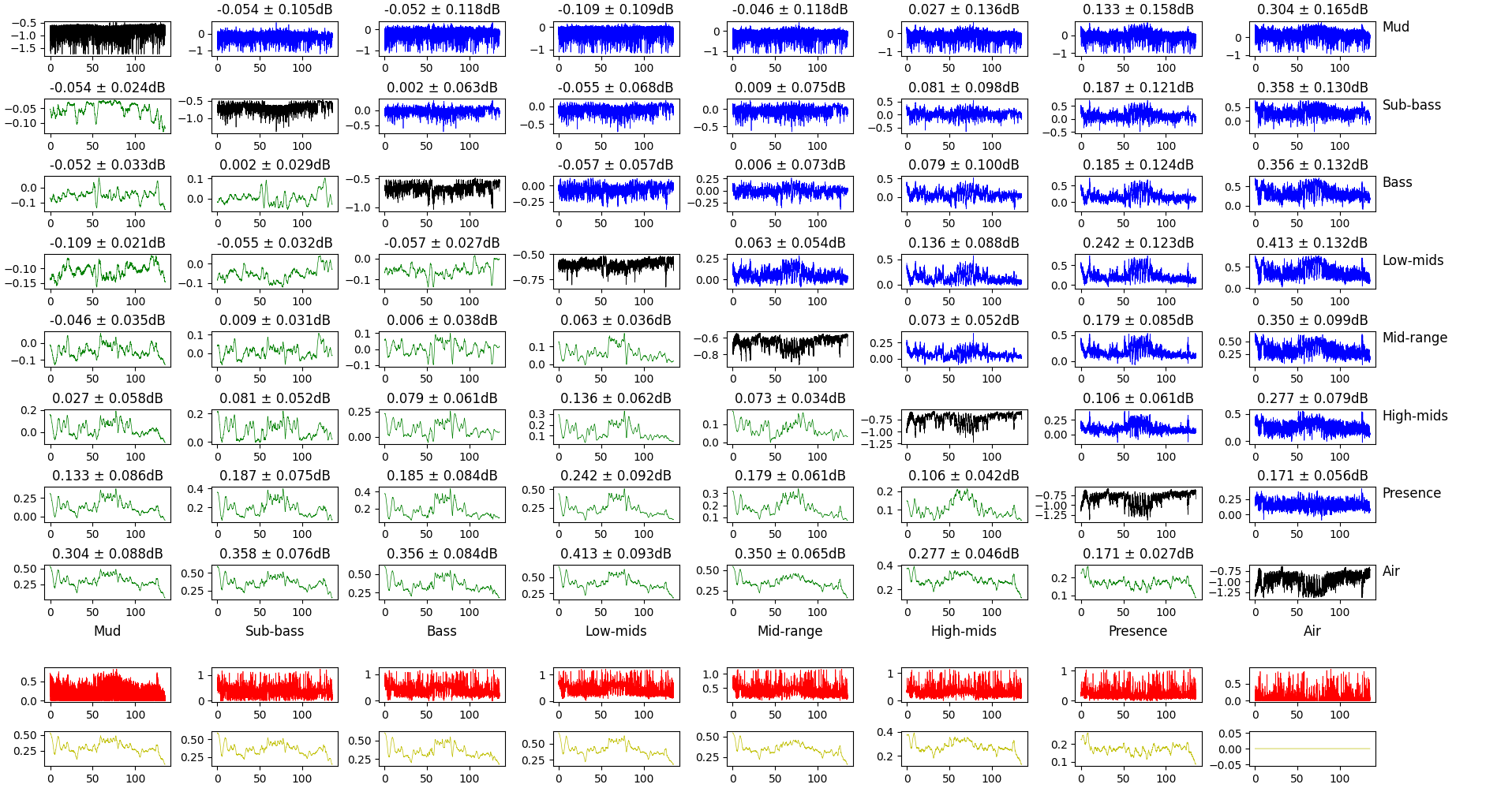

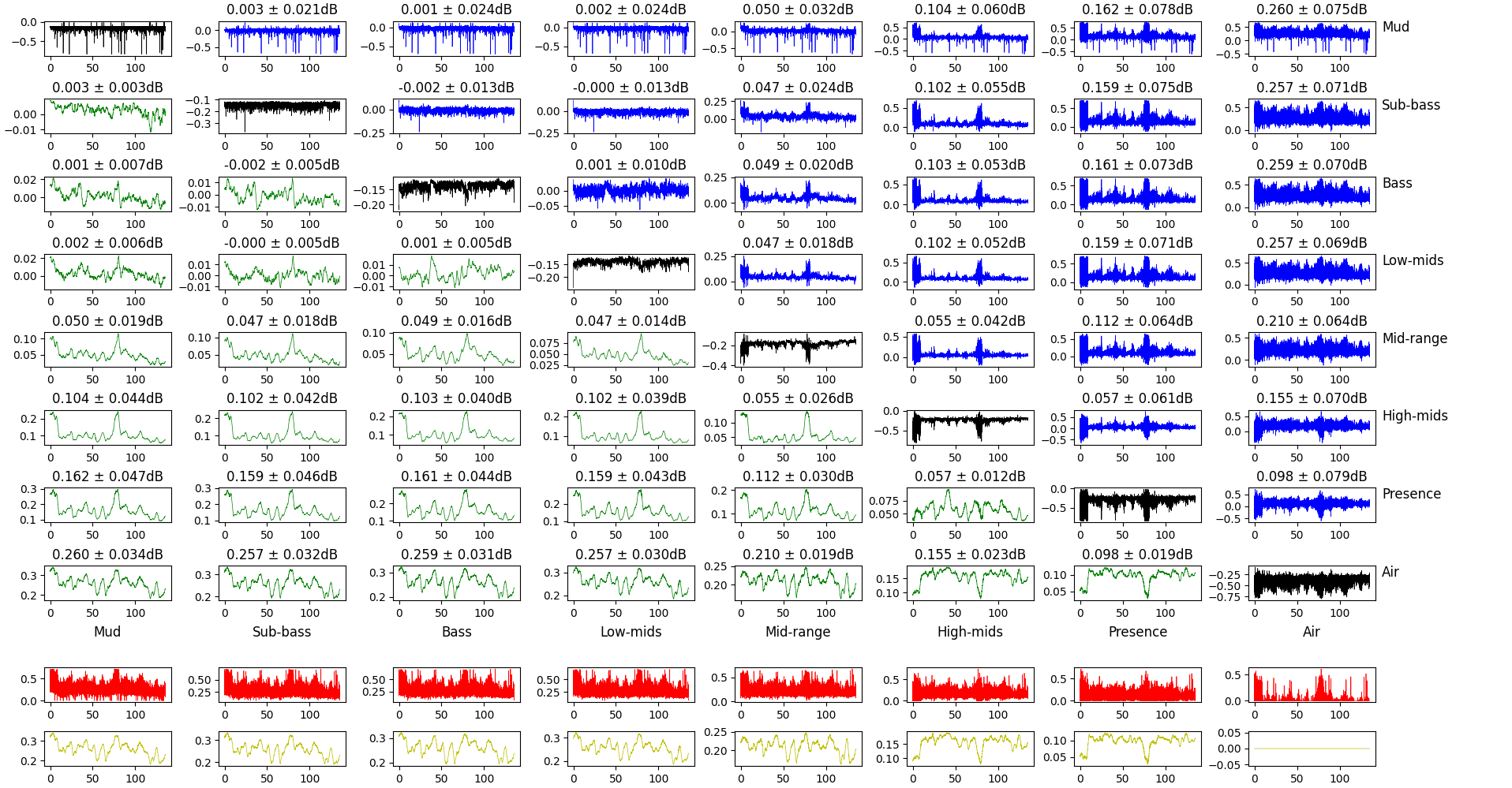

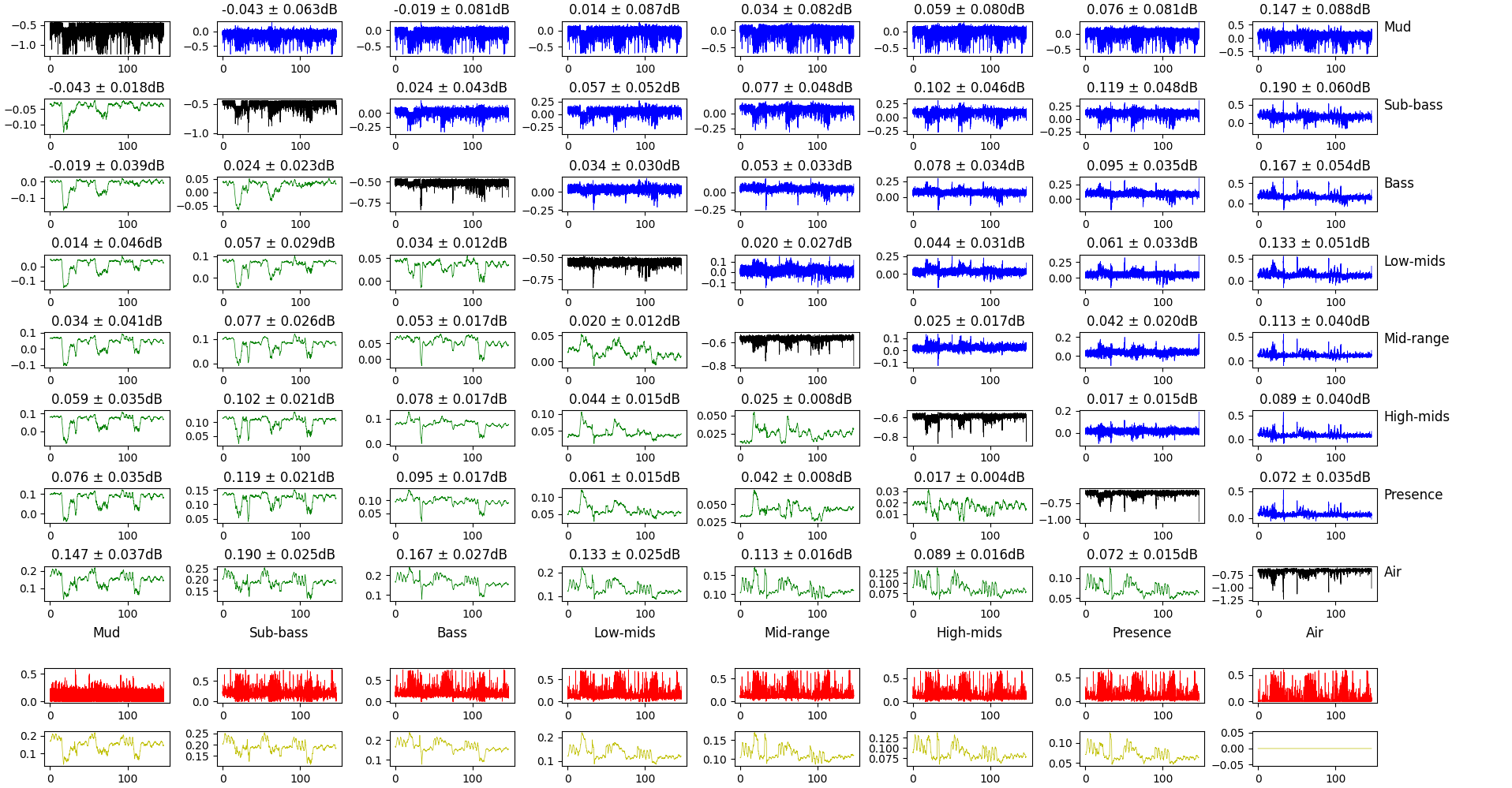

Comparison of the gain of different frequency bands.

Comparison of the gain of different frequency bands.

This plot is a bit dense, so let’s break it down. The top square of plots features:

- in the diagonal, the gain for this frequency band (lower value means more attenuation after volume normalization);

- in the top-half, the difference between the gains of different frequency bands (the difference is lower frequency - higher frequency);

- in the bottom half, the same difference, but smoothed in time over 20ms.

The bottom rows show the maximum difference of the gain for this frequency band and all the others. Raw for the top one, smoothed over 20ms for the bottom one.

What we’re tying to get here is if some frequency band gets sacrificed for another and if so, when. Interestingly, some of the big changes happen when the music shifts from loud to quiet and vice-verse, but not always. Lower frequencies respond more to these big changes than mids and treble.

What this ultimately means and what we can deduce from the underlying algorithm is a bit out of reach right now, but it’s nonetheless an interesting observation.

Reproducibility

Now, it’s all well and good to do this on one track, but we can gather data for more recordings, of different styles. The next tracks I will analyze will be the following:

| Title | Album | Artist | Genre |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altered Perspective Two | Alone | Evan Brewer | Instrumental |

| Muma | AD:Trance 10 | Nhato | Trance |

| MARVYN | MARVYN | Changeline | Rap |

| Non, je ne regrette rien | Platinum Collection | Édith Piaf | French oldie |

| 3 Gyménopédies: No. 1, Lent et Douloureux (Orch. Ducros) | Émotions | Gautier Capuçon | Classical |

They are chosen quite arbitrarily, but the aim is to get titles which are quite different to get at least somewhat of a decent sample. Let’s show the results below, quickly. For each title, I’ll show the three same figures as before, and I’ll draw a global conclusion after.

Altered Perspective Two

Muma

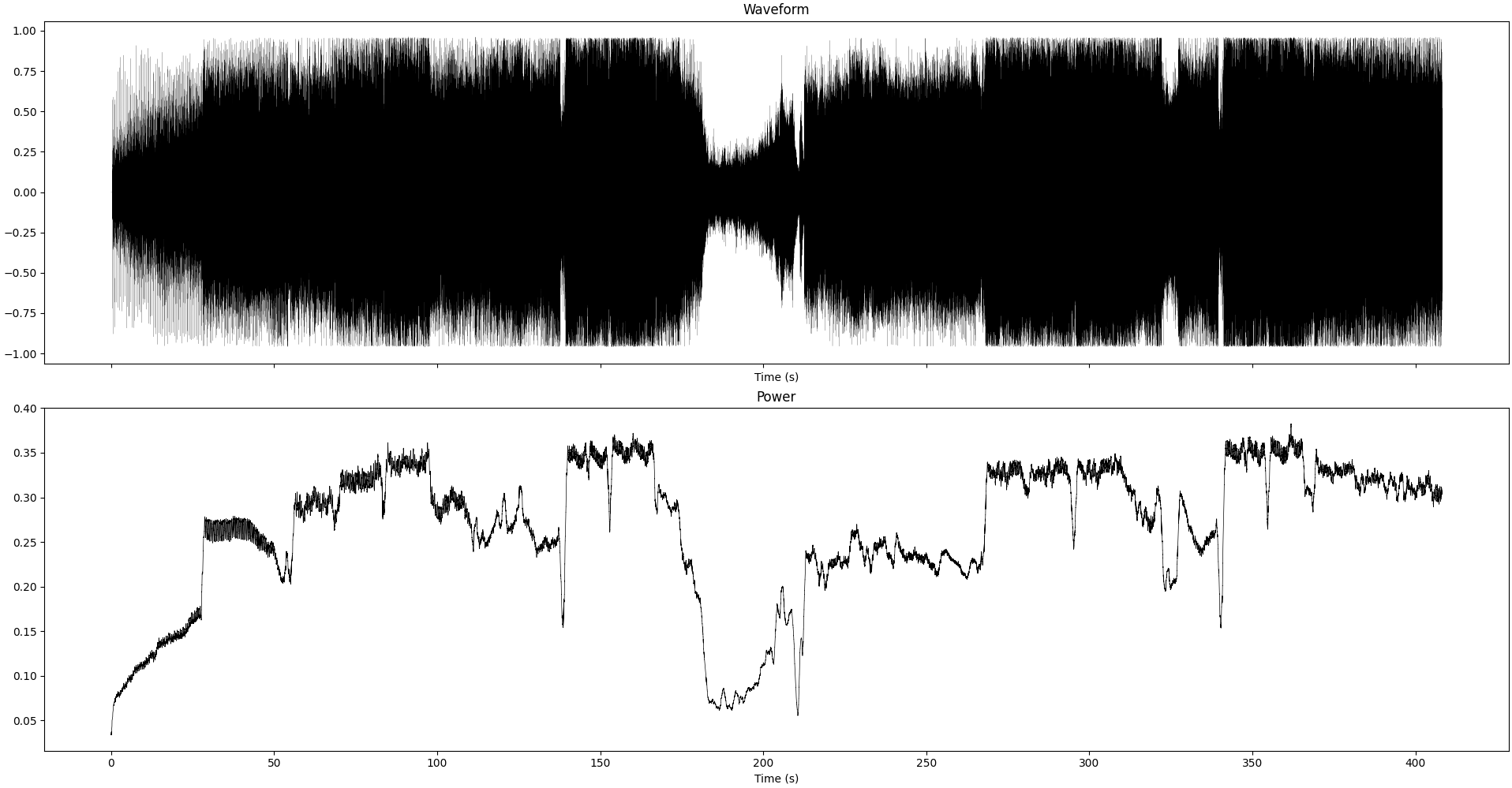

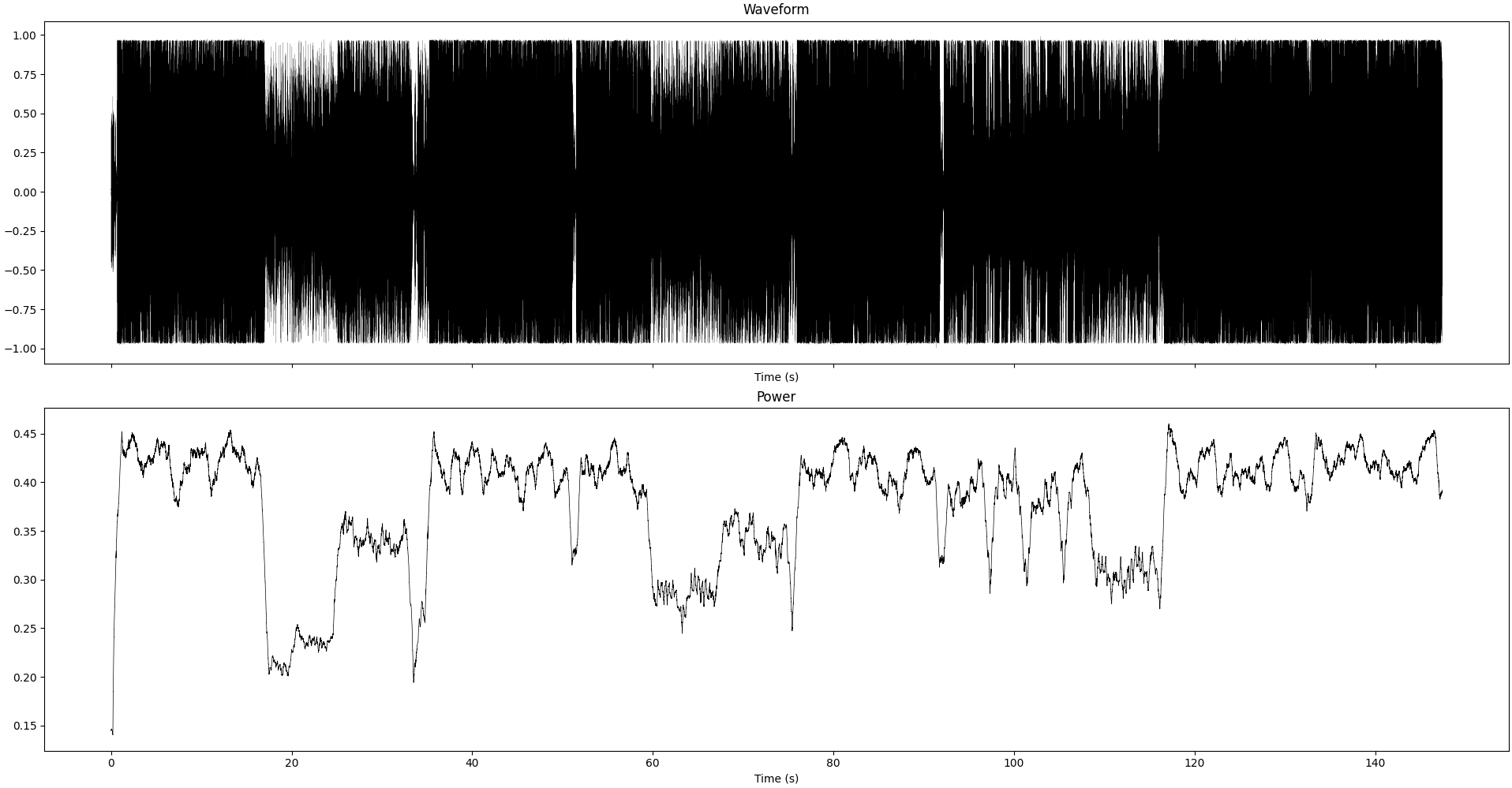

MARVYN

Non, je ne regrette rien

Gyménopédies

Conclusion

From all these recordings, we can confirm that there is some change in the sound. The effect is roughly the same on every recording, a change in 1~5% of the relative power of the frequency band due to the volume normalization.

It also seems to be sensitive to the overall power of the track: patterns in the power are preserved in the effect we see from volume normalization. In particular, quiet parts seem to have their treble boosted and their bass lowered, and vice-versa.

I wanted to include some personal notes from my listening of these tracks as well. People who’ve been next to me when I listen to music can attest as such, I usually listen to music very loud in my headphones. I know it’s not great, but it’s not the topic. Listening to music very loud often means contending with the limits of what my headphones can accurately render, and having some saturation going on. I was half-expecting that wuth volume normalization, because the waveform is ~2x as energetic as witout, saturation would go away. But as a matter of fact, for some tracks it got worse! I think the worst was for MARVYN. I know my headphones mostly saturate on high-frequencies, so the increase in treble due to the volume normalization really explains why it was so painful to listen to this way.

Interpretation

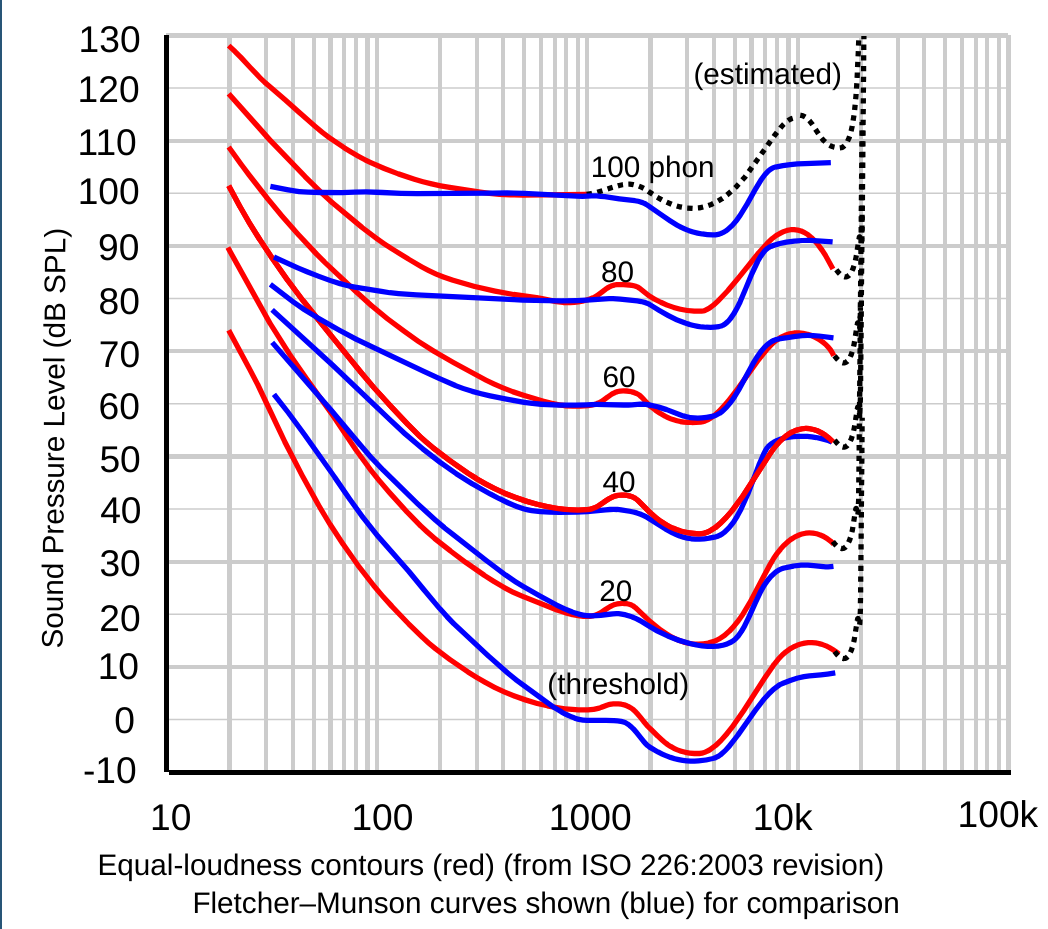

An idea as to why quiet parts have their trebled empowered while their bass is dimished is psychoacoustics. The human ear does not process all frequencies the same. After all, we’re mainly “designed” to react to human speech and nature sounds, which lie mostly in the mids. So, psychoacoustic research gives us some insight as to how sensitive we are to some frequencies compared to others. The subject is quite vast, and prone to refinements ad infinitum, so we’ll only consider one aspect of it: equal-loudness contours.

Defined in the ISO 226 norm, equal-loudness contours basically give us a set of (frequency, air pressure level in dB) that “all seem as loud as each other”. The exact details of the definition doesn’t really matter here, what does matter is that we tend to percieve bass as not very loud and high-mids/treble as quite loud. The contour changes a bit of shape depending on the loudness level we consider as well, we are less sensitive to changes in bass for example.

Equal loudness contours as defined in the ISO 226 norm. Image from Wikimedia

Equal loudness contours as defined in the ISO 226 norm. Image from Wikimedia

All this is coherent with the decisions made by engineers when they designed the volume normalization. By choosing not to reduce the intensity of the signal uniformly across all frequencies, but to adjust to the loudness of the current part of the song, we can artificially make the track seem louder or quieter than it actually is.

It’s quite clever, but it introduces one major artifact: harmonics distortion. As you may know, a single sound has a specific fundamental frequency and harmonics (integer-multiple of the fundamental). So, a piano and a guitar may play a 440Hz A, both will have the same fundamental but different harmonics.

Here’s the issue, if you choose to scale one frequency band differently than another, it means that the harmonics will be changed as well. In our case, it’s not changed enough to really change how we interpret the sound, but it can make it seem a bit different. Less warm, less full, more restrained… It’s very qualitative and subjective, so I will let you give the words that feel adequate for your experience.

tl;dr: my guess is that the volume normalization tries to take into account some psychoacoustics to trick the ear into having a similar loudness with a more constrained waveform, but messes with the harmonics in the process.

Conclusion

While the exact algorithm of volume normalization is unclear and properly reverse-engineering it is way out of league – whether thinking time, motivation or skills – it is quite clear that it changes the feel of the music. This is due to a change in the relative power of the different frequency bands, treble is heightened during quiet parts and bass is heightened during loud parts.

In my experience, I had mixed results when it comes to listening to music with and without volume normalization. With proper sound equipment (a half-decent headset counts here), I think removing the option improves the quality of the sound. Without such equipment, such as when listening directly on the speaker of a phone, I found that enabling volume normalization on the contrary helped quite a bit to avoid saturation.

I think the option is there for a reason. I would argue that it’s not really well labeled and it’s quite unclear what it does from the context of the app. But please try with and without the option for your favorite music, you’ll hear a difference and you can choose which setting fits you best.

Source code

All the souce code is available on my GitHub.

-

Even in this case, we may see some fluctuations because both recordings are encoded on 16 bit integers. Reducing the amplitude means reducing the precision, so there’s some “bit-noise” thrown in there as well. ↩︎